Jonathan Sanchez

From Curios to Culture

(The Heard Museum, Phoenix and what it can tell us about the ever changing state of Native American art.)

(The following is a research paper created for the UF Art Education program it was my final indie project for ARE 6048)

The process of contact that is to say Europeans, Asians and Africans learning of the multitude of languages, traditions, and art of the Americas is still on going. Manifest Destiny and its mania to create a country from sea to shining sea still reverberates with the folks in between those two coasts. Like all subcultures there is a push and pull from a dominant culture some ground is lost, some gained. The languages and traditions that are lost become fuel for the speculations of archaeologist, those that study dead cultures. But like so many sherds of pottery you can not know what was once cooked in the scattered pot, who sat around it, what was said or sung around the pot. Prevention is better than cure and preservation always preferred to recreation which brings us to the importance of the Heard Museum Phoenix.

Using the Heard Museum in Phoenix Arizona as a point of discussion I will present the evolution of Native arts and changing views of American Indian art while focusing specifically on the approach and methodology the Heard employs with regard to art education. The Heard provides an important repository of historic and contemporary items but also presents a unique art education perspective. Through the Heard’s continued efforts we can observe a model of multicultural and pluralistic art education in action.

The main achievements and contributions of the Heard to art education, are community outreach, preservation, creating a new standard and climate of multicultural education. They have reached these new levels and contributed to an overall discussion through direct tribal, peer, academic and community input. Hosting conferences, workshops, and displays intended to advance global understanding of the issues facing Native Americans as expressed through their art. The Heard took a historic stance but has not remained fixed it continues to contribute and shape advise and of course educate.

A Brief History

"The mission of the Heard Museum is to educate people about the arts, heritage and life ways of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, with an emphasis on American Indian tribes of the Southwest" (Heard Museum website).

It was a small effort that grew like the Phoenix area itself. Now a major densely populated city, so too the museum has grown in size, mission, and prestige. It was once a novel idea to gather a few Indian curios here and there with little thought to the ancient and rich cultures that spawned the works, the Heard was to treat these items differently. Dwight and Maie Bartlett Heard founded a small museum in 1929 in a little known area somewhere out west. The collections and facilities have grown over the many years that followed, shifting from a home for dusty things on a shelf to living breathing community center.

Maie Heard continued the museum after her husband’s death in late 1929, acting as custodian, lecturer, director, curator and a guide for more than 20 years. The Heard Museum underwent significant growth upon Maie Heard's death in 1951.

In 1956, the Heard Museum Auxiliary was established to assist with educational programs. Today, the Heard Museum Guild numbers nearly 700.

In 1958, volunteers launched two aggressive fundraising projects, adding a museum shop and a fair which today draws nearly 20,000 people from all over the world.

The Jacobson Gallery of Indian Art doubled the original building in the late 60's.

Today

The Dorrance Education Center includes three classrooms used for school tour orientations, specialized tours or workshops. Nearly 400 schools in 20 states use the Heard as a source of curriculum material about American Indian heritage, and 10,000 Arizona school children visit annually.

One of the most significant additions to the museum was the small Berlin gallery. It represents the final step in a process from Curios to Culture. Native contemporary art is presented not as trinkets or tourist items but as the intellectual, spiritual, and cultural work of relevant modern artists. Like many that enjoy the benefits of this experiment in self rule we call America, Native Americans exist within and without American culture. Arizona is fortunate to be home to 22 tribal nations, each with its own distinct language and cultural traditions.

The museum shops and market provide an outlet for Native crafts producers and allow artisans of all kinds to sell their items.

Rose Bean Simpson

Rose Bean Simpson

Art Education at the Heard

It is in many ways impossible to remove any art from its culture and have it retain its meaning. The Heard does an amazing balancing act, rhetorically, and physically to maintain the concepts behind the art and the deeper cultural ties, and still present their collections as works of art. Often there is a distinction made. Items are referred to as works of art but also as, "cultural items". When I spoke with a few of the docent about the distinction it was noted that some items were tourist trap pieces that though now old never held ceremonial or religious medicine. The works are presented for their aesthetic and historic merits. There is often a fine line between such distinctions but all comments and inferences about the works must begin from a perspective of respect and cultural sensitivity.

Excerpt from the Heard website.

"Nearly 2,000 treasures including jewelry, cultural items, pottery, baskets, textiles, beadwork and more."

The education department has been a part of the museum from the beginning with tours and lectures and in the 1950's expanding to wider programing. Today they have three kid friendly facilities, two jam packed with hands on activities for wide range of ages. Kids and families can interact with video, a variety of games and are encouraged to draw and create throughout the education areas. There are items for download through the website, there are others to take home to continue the process outside of the museum, and plenty to do an interact with while at the museum. There is a real mix of aesthetic activity and acknowledgment of the culture and stories behind the visual concepts. Clearly the Heard is a modern museum shaped by Native input and state of the art museum thinking, the result of long evolutionary process.

On the Trail of Leaps and Bounds

I visited the Phoenix Art Museum and Heard Museum libraries, education departments, and archives. The impetus for the Phoenix Art Museum visit was a photocopy of a program for a workshop that seems to have happened in 1991. It was a joint project between the Heard and the PAM. The PAM portion was centered around an exhibit of Western Art entitled Myths of the West. Cowboys both real and of the Hollywood varietal were contrasted. Romantic paintings of Bierstadt and others were compared to stark documentary photos and all of this accompanied with lectures on all things, "Out West" (1990, Rizzoli). They would also address the marginalized Native presence in genre paintings and the early studio or staged works of Indians that contributed to a mythic image of Native Americans (1991, Gray).

It has been a long process of allowing that Native Americans might have something to contribute other than posing for staged photos and paintings to satisfy white European fantasies about “Indians.” Natives held in captivity and allowed to draw or paint were at first mere curiosities (Heard Guide). Others in away schools attempting to solve the “indian problem through education” were forced to adapt European techniques of rendering and were largely deemed incapable of deeper intellectual processes (Stankiewicz, 48-49).  Away school exhibit the Heard

Away school exhibit the Heard

Contemporary artists, writers, performers, pushed back during the “Red Power Movement,” and opened some minds to Native perspectives.

The titles of the lectures perked my interest they seem to be exactly the sort stuff I was trying to unearth. Here are some excerpts.

Teaching Through Diversity (Leaps and Bounds) May 1st 1992 Phoenix Art Museum and Heard Museum

Program outline

"How do we approach the objects as art or artifact?

"Whose voice interprets the object?"

"How much do you need to know to interpret the object (or appreciate the object)?"

"Can a true understanding of an object from one culture be understood by another?"

"How do we teach sensitivity to and from other cultures?"

"What teaching methods do we use?"

"Are there any role models which we can follow?"

Sadly none of the papers made it into the archives of either museum, or anything more than that original photocopy survived the workshop. None the less these are all great questions to consider as art educators and were later transposed into the Museums Resource Guide.

I spoke with the PAM registrar and archivist and found that early Native works were out of the scope of the PAM's collecting. Native items of any kind were passed onto the Heard. I found this curious sure they have the corner on the market, the Heard works in conjunction with numerous tribes and tribal officials and the PAM has curators trained in other things ill-equipped to address Native art of a historic nature. But Scholder and others they were fair game, they were producing relevant contemporary art with Euro, Pop, and American references. They had it seems crossed an invisible line and were considered, "real art" worthy of a "real art collections or museums”.

PAM was ready to accept modern Native artists of a certain notoriety and caliber into their museum collection. I sat pondering this for some time and it still makes my head spin a bit, is this progress?

Back at the Heard

Like all museums the Heard is dependent on the generosity of the general public. In the retirement Mecca of Arizona some of that generosity comes in the form of volunteers. A team of docents, guides, and general workers, allow the museum to function. I sat with a few of these docents to glean what I could about their training process, their attitudes toward the objects, and what they felt the museums goals were. All agreed that education was primary to the museum and that it was key to the survival of Native cultural ways. A re-education process was needed to help people re-learn or abandoned the often racist views that the general public hold about Native Americans.

Native images are all over the place in America from carved wooden figures, western movies, and sports mascots, but like other racial stereotypes of the past they tell us nothing of the actual people they characterize. The real challenge of the Heard is to use art and art education to break down these stereotypes and help the museum public, and the larger community walk away with a new understanding and respect.

Walking through the museum people watching and listening to the general public, I found younger people more open minded in this regard and the senior groups visiting, mouthing the old cliches, and even racial epitaphs. Ironically many of the museum workers are Native and must have to daily endure these slurs and cliches. One contrasting view was expressed by a young teenage girl that while viewing items from Pacific northwestern tribes stated, "Now I like these indians, I hate the ones in the Southwest." That is to say the Indians she encounters on a daily basis she claimed to hate versus the ones far away that she had no contact with.

The docents I spoke with seemed guarded and very careful of what they said and how they said it. They undergo an extensive training beginning with cultural sensitivity to combat the years of John Wayne films and sports mascots. Two years later some one is fully certified as a docent and must continue to be quizzed, observed, and tested routinely. They are presented a script of highlights or talking points but are encouraged to make the tours and talks their own over time. Respect, and approaching the art as part of a universal urge to create and make art continued return to the discussion. I left with the sense that the staff felt they were held up in a stronghold of ideas expressed through art. A stronghold besieged by overwhelming misinformation, racism, stereotypes, and “other” making forces. Art a kind of hostage in a larger cultural struggle can often be lost beneath the politics.

At the Heard looking for the origins of modern native art, a change in attitude or rhetoric, some clue as to when the shift from Curios to Culture actually occurred, I ran into some interesting historic documents.

AAM ICOM NAGPRA and the Politics of Culture

The 1970's saw sweeping legislation with far reaching and snowballing effects for the museum world. By laws were revised, codes modified, new ones written and museums from the top down are still reverberating from the shift. President Carter in 1978 signed into action Senate Joint Resolution 102 (Law No. 95-341, Heard Archives). The American Indian Religious Freedom Act was intended to reaffirm the rights tribes should have had under the US Constitution (Amendment 1). As these rights are guaranteed to all citizens in some cases it was defining Native people as such (versus enemy combatants, prisoners of war and the other quasi statuses some tribes held). For example, many southwestern American Indians returned from the second world war and found they had no right to vote (Navajo Code Talkers display, Heard Museum). American Indians were given back land during this time, and museums found themselves in conflict being mandated to return portions of their collections.

A Phoenix Gazette article in 1986 quotes then Heard director, Peter Walsh as saying, "It's been years since the Heard had any bones," that is to say human remains in its collection. The assumption is these items were long ago returned, handed over to tribal authorities or religious leaders. The inference is of course that they once had these things. Further, the question as to how many museums in 1987 when the article was published still had these items. Of the three southwestern museums that I have worked for as late as 1999 I can tell you that human remains were still in all three collections. At one museum I was blessed (smudged) by a Lakota medicine woman smoked the peace pipe, and given special instructions on how to treat and relocate the small collection of folks they were in possession of. A ceremony of cleansing, council advisement, tribal input and compliance from the staff, all to keep a few touchy items in the museums collection, what were other museums going through I wondered? We were willing to do these things out of respect though the few large funerary urns were once merely pretty pots.

The International Council on Museums convened to update and modify their stance with regards to the ethical treatment of cultural items. Similarly the American Association of Museums (AAM) decided to also review its 1922 charter and set of codes beginning in the 1970's. One of the key conferences was in fact held at the Heard in 1980 in conjunction with the National of American Indian Museums Association.

AAM Ethics Mandate was issued in 1987 stating, "Museums in the broadest sense, are institutions which hold their possessions in trust for all mankind and for the future of the human race." The resulting mandates and entire 30 page directive for the handling and possible return of sacred items. Here again is the rub a pleasing pot in a display case that is treated as a work of art might need to come out of the display case, might need to be treated differently or might need to be returned to a tribe altogether. Worldwide indigenous people watched these events annual meetings ensued and tribal people of all kinds began to assert their rights to their material culture in some cases their art.

Finally the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted in 1990, adding further and greater legal power to tribal organizations and officials.

The Native American Fine Arts Movement

The Heard has comprised one of its most valuable and available items the Resource Guide. Through the museums education section on its website, anyone anywhere can obtain a concise history of Native American art to present. Outlining the major movements and artists from the 1800’s and early interest in Native art to contemporary giants like Fritz Scholder and Rose Bean Simpson.

Through the hatred, relocation, broken treaties, rape, murder, theft, disease, starvation and outright genocide that has been the Columbian exchange, Native artists have still found the strength to create and add their unique voices to art history. To blame the shift from Curios to Culture purely on legislation is to deny that Native artist themselves used their art to protest, shape and change minds and perhaps influence legislation.

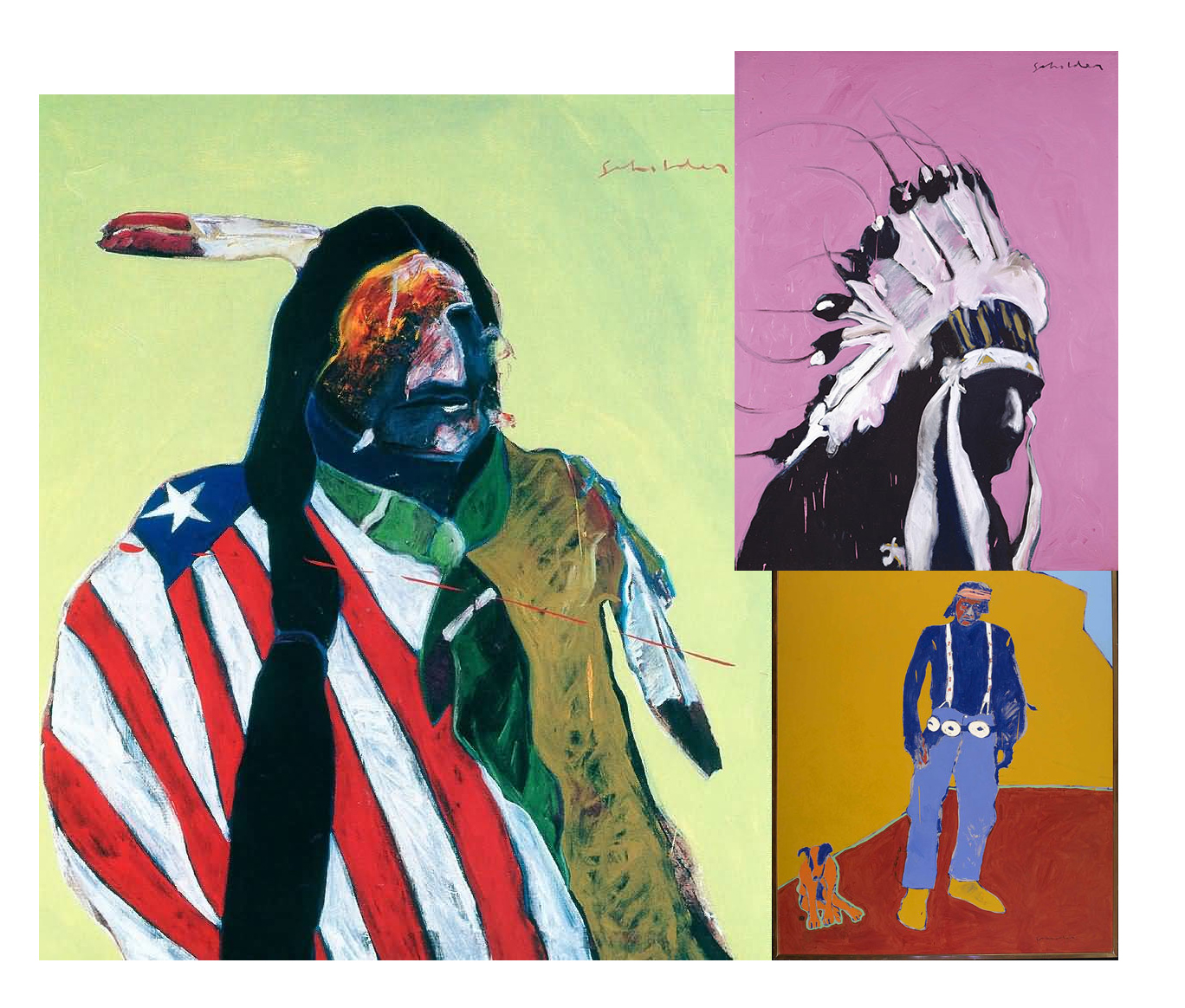

. Fritz Scholder

Fritz Scholder

.

There are too many fantastic contemporary Native artists to mention but the example of Fritz Scholder is worth mentioning. His works grace the walls of numerous fine art museums he has been recognized and has ascended to a lofty place in the art world. His work as an art educator in Santa Fe helped shape a generation of young artists and his social and political critiques rocked the foundations of the art world.

Central to his art was the notion of being Native in the modern world, questioning assumptions of what is Indian, what it means to be Indian? He drew from this unique perspective to challenge existing notions about Native Americans and bring about and acceptance on different terms. The bravery of Scholder and countless others drove the shift from Curios to Culture it was their activism and criticism that broke down the barriers of the art world. The Heard celebrates this spirit and lives out these themes.

The Heard is an experiment in Native art education presented and created with Native artists, tribal officials and scholars jointly. That it is has managed to endure and flourish is remarkable and its preservation efforts have allowed for future generations to experience a wide range of cultural items. Most importantly is the community and culture of respect that the museum represents putting its educational mission into to action.

References further reading;

Masterpieces of Western American Art (1991) Gray, J. M&M Books.

Myth of the West, (1990) Rizzoli, NY.

Institute of American Indian Arts.

Stankiewicz, M.A. (2001) Roots of Art Education, Davis Publication.

Blandy, D (2008) Studies in Art Education, Vol. 50 #1 (Phoenix Art Museum archive)

Discussions with the PAM archivist and registrar

No Bones (1997) Phoenix Gazette

Deloria V. (2003)God is Red. Fulcrum Publishing

Shared Visions: Twentieth Century Native American Painters and Sculptors in the United States (1993). The New Press, W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

NAGPRA website http://www.cr.nps.gov/nagpra/ Heard Museum displays or archive

Joint Resolution 102 public (Law No. 95-341, Heard Archives)

Navajo Code Talkers (display)

Home (display)

Interviews with staff and docents.

Overheard conversations while visiting the Heard.

Notes from the Heard Conference of Native American Indian Museums Association 1980 (archive)

American Association of Museums, notes from the 1987 Conference, section entitled, “Code of Ethics for Museums (archive)

Notes from the ICOM Conference 1986 on ethics. (archive)

AAM literature on the history of the AAM (archive)

Post script

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048) is a United States federal law enacted on 16 November 1990. The Act requires federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding (such as national parks) to return Native American "cultural items" to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. Cultural items according to the NAGPRA website are defined as, “human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.” A program of federal grants assists in the repatriation process and the Secretary of the Interior may assess civil penalties on institutions that fail to comply.

NAGPRA also establishes procedures for the inadvertent discovery or planned excavation of Native American cultural items on federal or tribal lands. While these provisions do not apply to discoveries or excavations on private or state lands, the collection provisions of the Act may apply to Native American cultural items if they come under the control of an institution that receives federal funding.

Lastly, NAGPRA makes it a criminal offense to traffic in Native American human remains without right of possession or in Native American cultural items obtained in violation of the Act. Penalties for a first offense may result in 12 months imprisonment and a $100,000 fine.

PSS

Ironically I ran into one of our own Doug Blandy in the PAM archives, well a paper from him. It was part of a larger workshop on Pluralism creating a culture of pluralism through art education. The situation of the lost papers which seem to answer my every research question and meet my goals was addressed by Blandy. "Art educators' predilection is to focus on the problems and challenges of today without fully considering their antecedents or the larger history of the field. Our taste is now to act on this as a basis for deepening our historical knowledge and more fully understanding the genesis and evolution of the field" (Foreword to the symposium "Celebrating Pluralism"). Here was suddenly the goal of our current class, the goal of the paper and research at hand, and the goal of the missing workshop I was on the trail of, but they failed they did not pass this info on intact to future generations as Blandy suggested they should have.

All of the archivist involved looked embarrassed, flabbergasted, none the less the very thing Blandy warns us of had managed to happen, the information was lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment